Today, the Commission is proposing that Member States ease the current restrictions on non-essential travel into the EU to take into account the progress of vaccination campaigns and developments in the epidemiological situation worldwide.

The Commission proposes to allow entry to the EU for non-essential reasons not only for all persons coming from countries with a good epidemiological situation but also all people who have received the last recommended dose of an EU-authorised vaccine. This could be extended to vaccines having completed the WHO emergency use listing process. In addition, the Commission proposes to raise, in line with the evolution of the epidemiological situation in the EU, the threshold related to the number of new COVID-19 cases used to determine a list of countries from which all travel should be permitted. This should allow the Council to expand this list.

At the same time, the emergence of coronavirus variants of concern calls for continued vigilance. Therefore as counter-balance, the Commission proposes a new ‘emergency brake’ mechanism, to be coordinated at EU level and which would limit the risk of such variants entering the EU. This will allow Member States to act quickly and temporarily limit to a strict minimum all travel from affected countries for the time needed to put in place appropriate sanitary measures.

Non-essential travel for vaccinated travellers

The Commission proposes that Member States lift restrictions on non-essential travel for vaccinated persons travelling to the EU. This reflects the latest scientific advice showing that vaccination considerably helps to break the transmission chain.

Member States should allow travel into the EU of those people who have received, at least 14 days before arrival, the last recommended dose of a vaccine having received marketing authorisation in the EU. Member States could also extend this to those vaccinated with a vaccine having completed the WHO emergency use listing process. In addition, if Member States decide to waive the requirements to present a negative PCR test and/or to undergo quarantine for vaccinated persons on their territory, they should also waive such requirements for vacccinated travellers from outside the EU.

This should be facilitated once the Digital Green Certificate becomes operational, in line with the rules the Commission proposed on 17 March. In particular, travellers should be able to prove their vaccination status with a Digital Green Certificate issued by Member States’ authorities on an individual basis, or with another certificate recognised as equivalent by virtue of a Commission adequacy decision.

Until the Digital Green Certificate is operational, Member States should be able to accept certificates from non-EU countries based on national law, taking into account the ability to verify the authenticity, validity and integrity of the certificate and whether it contains all relevant data.

Member States could consider setting up a portal allowing travellers to ask for the recognition of a vaccination certificate issued by a non-EU country as reliable proof of vaccination and/or for the issuance of a Digital Green Certificate.

Children who are excluded from vaccination should be able to travel with their vaccinated parents if they have a negative PCR COVID-19 test taken at the earliest 72 hours before arrival area. In these cases, Member States could require additional testing after arrival.

Full lifting of non-essential travel restriction from more countries

Non-essential travel regardless of individual vaccination status is currently permitted from 7 countries with a good epidemiological situation. This list is decided by the Council on the basis of epidemiological criteria contained in the current recommendation.

The Commission is proposing to amend the criteria to take into account the mounting evidence of the positive impact of vaccination campaigns. The proposal is to increase the threshold of 14-day cumulative COVID-19 case notification rate from 25 to 100. This remains considerably below the current EU average, which is over 420.

The adapted threshold should allow the Council to expand the list of countries from which non-essential travel is permitted regardless of vaccination status, subject to health-related measures such as testing and/or quarantine. As now, the Council should review this list at least every 2 weeks.

Essential travel to remain permitted

Those travelling for essential reasons, including notably healthcare professionals, cross-border workers, seasonal agricultural workers, transport staff and seafarers, passengers in transit, those travelling for imperative family reasons or those coming to study should continue to be allowed to enter the EU, regardless of whether they are vaccinated or which country they come from. The same applies to EU citizens and long-term residents as well as their family members. Such travel should continue to be subject to health-related measures, such as testing and quarantine as decided by Member States.

‘Emergency brake’ to counter the spread of variants

When the epidemiological situation of a non-EU country worsens quickly and in particular if a variant of concern or interest is detected, a Member State can urgently and temporarily suspend all inbound travel by non-EU citizens resident in such a country. The only exceptions in this case would be healthcare professionals, transport personnel, diplomats, transit passengers, those travelling for imperative family reasons, seafarers, and persons in need of international protection or for other humanitarian reasons. Such travellers should be subject to strict testing and quarantine arrangements even if they have been vaccinated.

When a Member State applies such restrictions, the Member States meeting within the Council structures should review the situation together in a coordinated manner and in close cooperation with the Commission, and they should continue doing so at least every 2 weeks.

Next steps

It is now for the Council to consider this proposal. A first discussion is scheduled at technical level in the Council’s integrated political crisis response (IPCR) meeting taking place on 4 May, followed by a discussion at the meeting of EU Ambassadors (Coreper) on 5 May.

Once the proposal is adopted by the Council, it will be for Member States to implement the measures set out in the recommendation. The Council should review the list of non-EU countries exempted from the travel restriction in light of the updated criteria and continue doing so every 2 weeks.

Background

A temporary restriction on non-essential travel to the EU is currently in place from many non-EU countries, based on a recommendation agreed by the Council. The Council regularly reviews, and where relevant updates, the list of countries from where travel is possible, based on the evaluation of the health situation.

This restriction covers non-essential travel only. Those who have an essential reason to come to Europe should continue to be able to do so. The categories of travellers with an essential function or need are listed in Annex II of the Council Recommendation. EU citizens and long-term residents as well as their family members should also be allowed to enter the EU.

Following a proposal by the Commission, the Council agreed on 2 February 2021 additional safeguards and restrictions for international travellers into the EU, aimed at ensuring that essential travel to the EU continues safely in the context of the emergence of new coronavirus variants and the volatile health situation worldwide. These continue to apply.

On 17 March 2021, in a Communication on a common path to Europe’s safe re-opening, the Commission committed to keeping the operation of the Council Recommendation on the temporary restriction on non-essential travel into the EU under close review, and propose amendments in line with relevant developments. Today’s proposal updates the Council recommendation.

In parallel to preparing for the resumption of international travel for vaccinated travellers, the Commission proposed on 17 March 2021 to create a Digital Green Certificate, showing proof that a person has been vaccinated against COVID-19, received a negative test result or recovered from COVID-19, to help facilitate safe and free movement inside the EU. This proposal also provides the basis for recognising non-EU countries’ vaccination certificates.

The Council Recommendation on the temporary restriction on non-essential travel into the EU relates to entry into the EU. When deciding whether restrictions on non-essential travel can be lifted for a specific non-EU country, Member States should take account of the reciprocity granted to EU countries. This is a separate issue from that of the recognition of certificates issued by non-EU countries under the Digital Green Certificate.

The Council recommendation covers all Member States (except Ireland), as well as the 4 non-EU states that have joined the Schengen area: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. For the purpose of the travel restriction, these countries are covered in a similar way as the Member States.

The latest information on the rules applying to entry from non-EU countries as communicated by Member States are available on the Re-open EU website.

For More Information

Proposal for a Council Recommendation on the temporary restriction on non-essential travel into the EU and the possible lifting of such restriction, 3 May 2021

Travel during the coronavirus pandemic

Compliments of the European Commission.

The post Coronavirus: Commission proposes to ease restrictions on non-essential travel to the EU while addressing variants through new ‘emergency brake’ mechanism first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.

EACC & Member News

In the second half of 2020 global economic activity and trade staged a sharp rebound driven mainly by the manufacturing sector, while services sector activity was and has remained subdued. In the third quarter of 2020 global economic activity recovered swiftly as a result of the easing of the pandemic and associated containment measures as well as the significant policy support deployed at the peak of the crisis. Despite a slowdown in the last quarter of the year, reflecting a worsening of the pandemic, the pace of the global economic recovery in the second half of 2020 was overall stronger than initially estimated (ECB 2021, IMF 2021).[1] It was driven to a significant extent by the manufacturing sector (Chart A, upper panel), as production activities restarted and the demand for goods recovered. At the same time the services sector, and especially the most contact-intensive activities, lagged behind owing to continued social distancing and some remaining limitations. These also hit the travel and tourism sectors particularly hard. Following the collapse in global trade in the first half of 2020 (ECB 2020), global merchandise imports recovered, and by November 2020 they had reached their pre-crisis level again. [2] However, the recovery has progressed at different speeds across countries, with China – the first country to bring the virus under control – already returning to its pre-crisis level in June 2020 (Chart A, lower panel). It was only towards the end of the year that the recovery in trade started to spread to other key global economies.

Chart A

Developments in global economic activity and trade

Global merchandise trade and PMI indices

(left-hand scale year-on-year, percentage changes; right-hand scale diffusion indices)

Global merchandise trade and country contributions

(left-hand scale index, December 2019 = 100; right-hand scale contributions)

Sources: Markit, CPB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The global aggregate excludes the euro area. The latest observations are for March 2021 (PMI) and January 2021 (global merchandise trade).

The sharp rebound in global manufacturing activity caused a strong rise in international orders and resulted in some supply bottlenecks. Supply frictions are evidenced by rising supplier delivery times, which in turn are reflected in higher container shipping costs and, more generally, in higher input prices. In particular, the Global Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) for different manufacturing sub-sectors show how the sharp rebound in new orders for inputs of production since the trough in the second quarter of 2020 has been accompanied by a strong rise in supplier delivery times and an increase in input price pressures (Chart B). The sectors experiencing stronger disruptions in supply chains are basic materials, machinery and equipment, and cars. A particularly severe shortage in the supply of semiconductors is causing delays in car production globally.[3]

Chart B

Supplier delivery times and input prices

Global PMI Indices (diffusion indices)

(y-axis – PMI suppliers’ delivery times (reversed); x-axis – PMI new export orders, change between February 2021 and Q2 2020)

Sources: IHS Markit, Haver analytics and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The size of the bubbles is proportional to the change in the PMI index for input prices between February 2021 and Q2 2020. Grey dots reflect increases in the PMI index for input prices below 10, yellow dots reflect increases between 10 and 15 and blue dots reflect increases in the PMI index greater than 15.

Rising ocean freight shipping costs are another sign of supply bottlenecks (Chart C, upper panel). Since the second half of 2020, global freight shipping costs have been on a steady recovery path from the lows reached in the midst of the pandemic. In recent months, however, they have reached levels not seen since after the Great Financial Crisis, while growth rates have risen above those observed since 2015. At the same time, transport costs on shipping routes from Asia and China to Europe and the Mediterranean, as well as the United States, have experienced a particularly sharp rise since the second half of the year. They appear to have peaked recently (Chart C, lower panel). Two factors are associated with the increase in shipping costs. On the one hand, the strong rise in demand for intermediate inputs on the back of stronger manufacturing activity raised the demand for Chinese exports and the demand for container shipments. At the same time, shortages of containers at Asian ports have exacerbated supply bottlenecks and further increased shipping costs as companies in Asia are reported to be paying premium rates to get containers back.[4] Reportedly, ports in Europe and the United States are congested amid logistics disruptions related to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and idle containers remain in several ports on the back of the uneven recovery of trade. Notably, available data point to a decrease in container ship traffic from important Asian ports, with the Asia-EU trade lane having experienced the biggest decrease (as indicated by the largest reduction in Chart D). In this context, the reliability of the schedules of global container services has declined to the lowest levels on record, according to new data from SeaIntelligence Consulting.[5] The rise in shipping costs has been further exacerbated by limited air freight capacity as international flight volumes have plunged due to travel restrictions and flight cancellations.

Chart C

Global and regional shipping costs

Global shipping costs

(year-on-year, percentage changes)

Freightos Baltic Index

(USD per forty-foot equivalent unit shipping container, contributions of sub-indices)

Sources: Bloomberg, Refinitiv, and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for March 2021. The World Container Index (WCI) is a composite indicator of container freight rates for eight major trade lanes between Asia, Europe and North America. The China (Export) Containerized Freight Index (CCFI) is a composite indicator of container freight rates from all major ports in China. The Harpex is a composite indicator of weekly container shipping rate changes in the time charter market for eight different classes of container ships. The Freightos Baltic Global Container Freight Index (FBX) is a composite indicator of container freight spot rates across twelve major global trade lanes.

Chart D

Shipping capacity

(deadweight tons (DWT); 1 DWT=1,000 kilograms)

Sources: Bloomberg, IHS and ECB calculations.

Notes: Container ship vessels include container ro-ro cargo, container, deck cargo and general cargo vessels. Port of departure includes major Asian ports (Shanghai, Singapore, Shenzhen, Ningbo, Busan, Hong Kong and Klang). Port of destination, in addition to major Asian ports, includes major European ports (Rotterdam, Antwerp and Hamburg), major North American ports (Los Angeles, Long Beach and New York/New Jersey) and major South American ports (Santos, Colon and Cartagena). Shaded areas refer to the volume of traffic – when vessels are fully loaded – in April 2020, whereas the solid areas refer to the volume of traffic in February 2021. The thickness of edges is proportional to the aggregate deadweight tonnage (DWT) and percentages refer to the share of each destination out of total outbound DWT from Asia in April 2020 (shaded area) and February 2021 (solid areas) respectively.

The rise in global container shipping costs at the end of 2020 largely reflected stronger demand (Chart E). We use econometric analysis to disentangle the relative importance of the demand and supply forces.[6] The analysis suggests that at the start of 2020 supply constraints explained rising shipping costs, as containers were grounded as a consequence of the measures adopted to contain the spread of COVID-19. While such pressures persisted in the second quarter of the year, amid stringent containment measures globally, these were more than offset by the great trade collapse which led to a sharp decline in the Harpex. Shipping costs remained subdued in the third quarter as supply chain disruptions begun to subside, and global demand was on a path of gradual recovery and feeding only slowly into higher trade flows.[7] In the fourth quarter, however, the rise in shipping costs reflected above all the more vigorous recovery in global demand, and only to a smaller extent supply constraints in the shipping industry.[8] The surge in global oil and fuel prices further contributed to the spike in shipping costs.

Chart E

Historical decomposition of global shipping costs

(percentage point deviations from trend, contributions)

Sources: ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The decomposition is based on an SVAR model that employs: total shipping containers (measured in twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs)), Harper Peterson Charter Rates Index (Harpex) of shipping costs and fuel prices. The model is identified using sign restrictions whereby a positive demand shock leads to an increase in both TEUs and the Harpex, while a positive supply shock leads to an increase in TEUs and a decline the Harpex (both have no contemporaneous impact on the oil price). An oil price shock leads to an increase in the oil prices and the Harpex, and a decline in TEUs. The model is estimated on monthly data (expressed in annual dynamics) from January 2013 to January 2021.

The surge in shipping costs raised the question to what extent these are passed on through the pricing chain. Importers commonly pass on part of rising transportation costs to consumers through higher prices, which could give rise to inflationary pressures. In order to gauge the potential magnitude of this effect, a structural vector autoregressive (SVAR) model has been estimated for the US economy, following Herriford et al. (2016).[9] The analysis suggests that after one year, the pass-through of shipping prices into US Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) inflation is rather limited.[10] Even a 50% annual increase in the Harpex – similar to that experienced leading up to January 2021 – could raise annual PCE inflation by up to 0.25 percentage points one year later. The size of this effect is also explained by the fact that international shipping costs make up only a relatively small share of the final cost of manufacturing output.[11] Overall, given that supply challenges are largely driven by transportation rather than production constraints, the rise in transportation costs is expected to have only a modest impact on global economic activity.[12]

As supply adjusts to higher demand freight costs might decline again. Overall, higher shipping costs and longer delivery times have caused temporary frictions in supply chains. However, as supply adjusts to increased demand, these bottlenecks should delay but not derail the global recovery.[13] At the same time, as lockdowns are lifted and consumers rebalance their spending towards services, some easing of the current supply bottlenecks should be expected, with knock-on effects on shipping costs.

Authors:

Maria Grazia Attinasi

Alina Bobasu

Rinalds Gerinovics

Compliments of the European Central Bank.

The post ECB | What is driving the recent surge in shipping costs? first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.

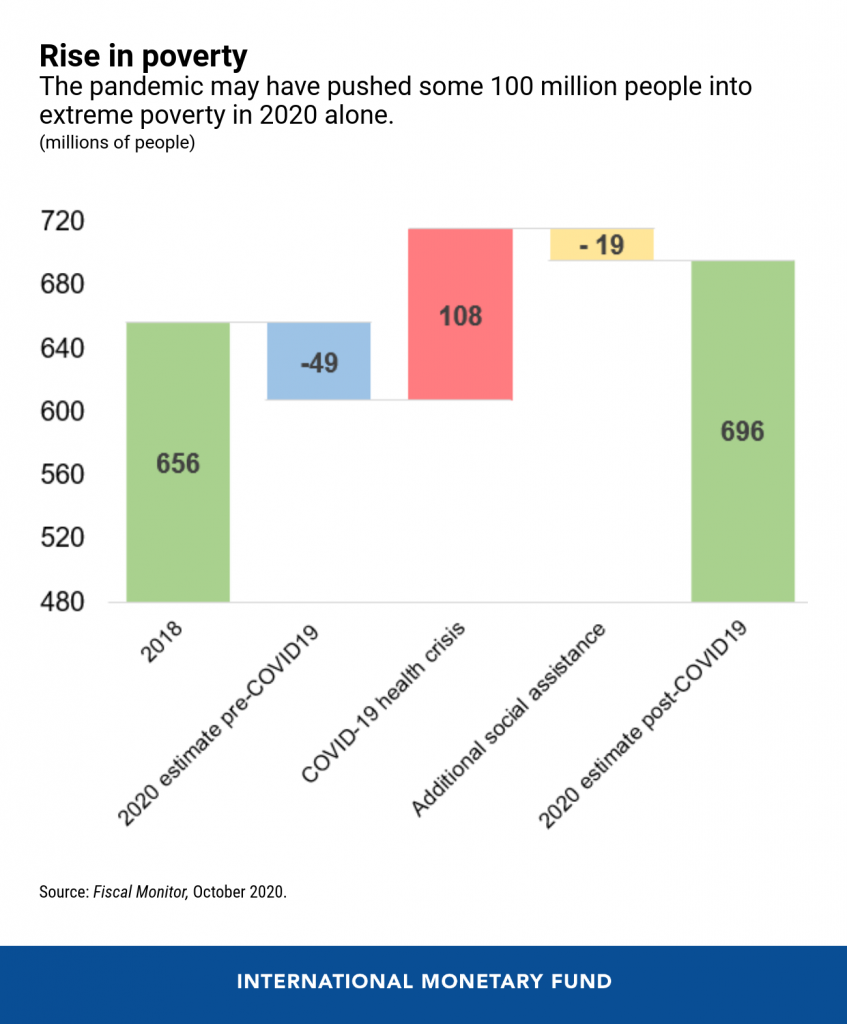

The pandemic’s impact on the world’s poor has been especially harsh. COVID-19 may have pushed about 100 million people into extreme poverty in 2020 alone, while the UN warns that in some regions poverty could rise to levels not seen in 30 years. The current crisis has derailed progress toward basic development goals, as low-income developing countries must now balance urgent spending to protect lives and livelihoods with longer-term investments in health, education, physical infrastructure, and other essential needs.

In a new study, we propose a framework for developing countries to evaluate policy choices that can raise long-term growth, mobilize more revenue, and attract private investments to help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Even with ambitious domestic reforms, most low-income developing countries will not be able to raise the necessary resources to finance these goals. They need decisive and extraordinary support from the international community—including private and official donors and international financial institutions.

Major setback

In 2000, global leaders set out to end poverty and create a path to prosperity and opportunity for all. These objectives were anchored by the Millennium Development Goals and 15 years later by the Sustainable Development Goals set out for 2030. The latter represent a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity, for people and the planet, now and into the future. They require significant investments in both human and physical capital.

Until recently, development progressed steadily, albeit unevenly, with measurable success in reducing poverty and child mortality. But even before the pandemic, many countries were not on track to meet the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. COVID-19 hit the development agenda hard, infecting more than 150 million people and killing over three million. It plunged the world into a severe recession, reversing income convergence trends between low-income developing countries and advanced economies.

The IMF has provided emergency financing of $110 billion to 86 countries, including 52 low-income recipients, since the pandemic started. We have committed $280 billion overall, and our planned general SDR allocation of $650 billion will benefit poor countries without adding to their debt burdens. The World Bank and other development partners have also offered support. But this alone is not enough.

In our paper, we develop a novel macroeconomic tool to help assess development financing strategies, including the financing of the Sustainable Development Goals. We focus on investment in social development and physical capital in five areas at the core of sustainable and inclusive growth—health, education, roads, electricity, and water and sanitation. These key development areas are the largest outlays in most government budgets.

We apply our framework to four countries—Cambodia, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Rwanda. These countries will, on average, need additional annual financing of over 14 percent of GDP to meet the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, some 2½ percentage points per year above the pre-pandemic level. Put differently, without increasing financing, COVID-19 may have delayed progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals by up to five years in the 4 countries.

The setback could be much larger if the pandemic results in permanent economic scarring. Lockdown measures have significantly slowed economic activity, depriving people of income and preventing children from attending school. We estimate that the long-lasting damage to an economy’s human capital, and hence growth potential, could increase the development financing needs by an additional 1.7 percentage points of GDP per year.

Meeting the challenge

How can countries hope to make meaningful progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals under these new, more difficult circumstances triggered by the pandemic?

It will not be easy. Countries will have to find the right balance between financing development and safeguarding debt sustainability, between long-term development objectives and pressing immediate needs, and between investing in people and upgrading infrastructure. They will have to continue attending to the matter at hand—managing the pandemic. At the same time, however, they will also need to pursue a highly ambitious reform agenda that prioritizes the following:

Fostering growth, which will start a virtuous circle. It enlarges the pie, resulting in additional resources for development, which in turn further spurs growth. Structural reforms that promote growth—including efforts to enhance macroeconomic stability, institutional quality, transparency, governance, and financial inclusion—are thus essential. Our study highlights how Nigeria and Pakistan’s strong growth enabled them to make significant strides in reducing extreme poverty prior to 2015. Jumpstarting growth, which has since stalled in these populous countries, will be crucial.

Strengthening the capacity to collect taxes is vital to pay for the basic public services that are necessary to achieve key development objectives. Experience shows that increasing the tax-to-GDP ratio by an average of 5 percentage points over the medium term through comprehensive tax policy and administration reforms is an ambitious but achievable objective for many developing countries. Cambodia has done it: in the 20 years leading up to the pandemic, it increased its tax revenue from less than 10 percent of GDP to around 25 percent of GDP.

Enhancing the efficiency of spending. About half of the spending on public investment in developing countries is wasted. Improving efficiency through better economic management together with enhanced transparency and governance will allow governments to achieve more with less.

Catalyzing private investment. Strengthening the institutional framework through better governance and a more robust regulatory environment will help catalyze additional private investment. Rwanda, for example, was able to increase private investment in the water and energy sectors from virtually nothing in 2005–09 to over 1½ percent of GDP per year in 2015–17.

Pursued in tandem, these reforms could generate up to half the resources needed to make substantial progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals. But even with such ambitious reform programs, we estimate that development objectives would be delayed by a decade or more in three of our four case study countries if they were to go it alone.

This is why it is critical for the international community to step up as well. If development partners gradually increase official development aid from the current 0.3 percent to the UN target of 0.7 percent of Gross National Income, many low-income developing countries may well be in a position to meet their development objectives by 2030 or shortly thereafter. Providing such assistance may be a tall order for policymakers in advanced economies, who are likely more focused right now on domestic challenges. But helping development is a worthy investment with potentially high returns for all. In the words of Joseph Stiglitz, the only true and sustainable prosperity is shared prosperity.

Compliments of the IMF.

The post IMF | Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals Will Require Extraordinary Effort by All first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.

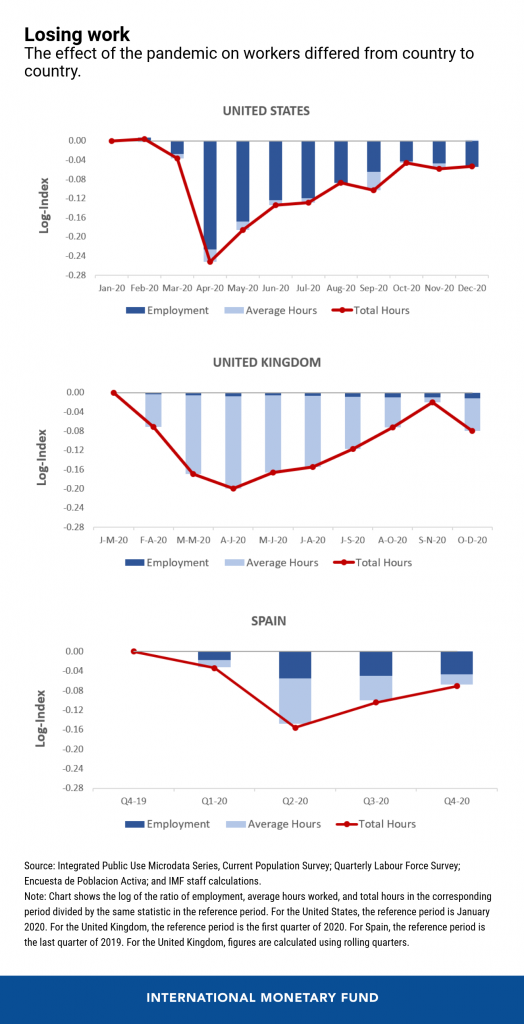

A year ago, the world changed. While the pandemic’s effect on workers has varied worldwide, the new reality has left many mothers scrambling. With schools and daycares closed, many were forced to leave their jobs or cut the hours they worked. New IMF estimates confirm the outsized impact on working mothers, and on the economy as a whole. In short, within the world of work, women with young children have been among the biggest casualties of the economic lockdowns.

‘Mothers of young children have been disproportionately affected by the lockdown.’

Three countries—the United States, the United Kingdom, and Spain—illustrate the varied impact of the pandemic on workers. These three countries were among the most heavily hit by the virus globally, but it is the United States that saw the most job losses. In comparison, UK workers experienced the largest cut in working hours, while in Spain, workers faced a mix of both job losses and reduced hours.

These differences were particularly pronounced in the first months of the crisis, and are partly due to differences in government policies. The United States favored supporting unemployed workers through higher unemployment benefits, and over longer periods, whereas the United Kingdom and Spain opted to use retention schemes to preserve ties between workers and employers.

Mothers hit the hardest

Workers’ experiences not only differ across countries but also across gender. As shown in IMF research, in the United States, women were affected more than men, in the United Kingdom it was the other way around, while in Spain men and women shared similar levels of pain.

Despite these differences, all three countries shared one thing in common: mothers of young children have been disproportionately affected by the lockdown and resulting containment measures. School closures and the start of remote learning heaped extra care responsibilities on parents, and particularly on mothers.

As a result, many women—who were largely shouldering the weight of childcare and housework even before the pandemic—left their jobs or cut the number of hours they worked.

Women with younger children have suffered larger job losses and/or drop in hours worked than other women and men in all three countries. In the United States, for example, being a mother of at least one child under 12 years old reduced the likelihood of being employed by 3 percentage points compared to a man in a similar family situation between April and December 2020.

Greater gender and income inequalities

Our study analyzes in close detail the labor market in the United States and finds that the burden on mothers with young children accounts for 45 percent of the increase in the total employment gender gap. This burden has also caused an economic loss estimated at almost 0.4 percent of output between April and November 2020.

The pandemic may end up aggravating not only gender but also income inequality. As we look deeper, mothers with less than a college degree and mothers of color lost or quit their jobs in larger numbers during the early stages of the pandemic, and they are coming back to work at a much slower pace than other groups of workers.

Support for mothers

Given the disproportionate impact of lockdowns and containment measures on mothers—especially those with young children, targeted measures are needed to ease their return to work.

Financial support: Supporting mothers who have lost their jobs, and struggle to survive and provide for their families is crucial. This can be done through measures such as tax credits for low-income households with children, extension of unemployment benefits, and childcare assistance.

Childcare and schools: Governments should also incorporate considerations for school reopening when formulating vaccination priority lists. The availability of childcare is crucial to enable mothers to participate in the labor market. Governments should prioritize the reopening of schools and childcare centers and reduce the likelihood of further school closures. This requires investing in infrastructure and procedures to ensure a safe and sustainable reopening of schools.

Reallocation policies: Mothers, and women in general, are more likely to occupy jobs that require face-to-face interaction. COVID-19 has disproportionately destroyed such jobs, and some of them won’t return. Therefore, governments should support workers in finding other jobs while minimizing their loss of human capital, through hiring subsidies and training programs, including tech training.

Access to finance: Increasing access to financial services could greatly help women to start/maintain their businesses. For this, tapping the potential of financial technology to achieve greater financial inclusion is essential, particularly in developing countries. Equal access to digital infrastructure, such as access to mobile and internet coverage—as well as greater financial and digital literacy—can be a game changer for women.

Mothers have played a crucial role during this pandemic, taking care of children, and absorbing many of the costs associated with the containment measures introduced to stop the spread of the virus. The recommendations outlined above are all the more imperative as the global economy still grapples with the recovery from the pandemic. In order to fully recover, the world economy needs to fully reintegrate women into the workforce.

Authors:

Kristalina Georgieva

Stefania Fabrizio

Diego B. P. Gomes

Marina M. Tavares

Compliments of the IMF.

The post IMF | COVID-19: The Moms’ Emergency first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.

The COVID-19 crisis has resulted in the largest decrease in taxes on wages since the global financial crisis of 2008-09, according to a new OECD report.

Taxing Wages 2021 shows that declining household incomes coupled with tax reforms linked to the pandemic are driving widespread declines in effective taxes on wages across the OECD.

The report highlights record falls across the OECD during 2020 in the tax wedge – the total taxes on labour paid by both employees and employers, minus family benefits, as a percentage of the labour cost to the employer.

The tax wedge for a single worker at the average wage was 34.6% in 2020, a decrease of 0.39 percentage points from the previous year. This is a significant fall, but is smaller than the decreases seen in the global financial crisis – 0.48 percentage point in 2008, and 0.52 percentage points in 2009. The tax wedge increased in 7 of the 37 OECD countries over the 2019-20 period and fell in 29, mainly due to lower income taxes.

The drop in the tax wedge was even more significant for households with children, bringing tax rates on these family types to new lows. The average tax wedge for a one-earner couple at the average wage with children in 2020 was 24.4%, a decrease of 1.1 percentage points versus 2019. This is the largest fall and lowest level seen for this household type since the OECD started producing Taxing Wages in 2000.

Between 2019 and 2020, the tax wedge for this household type decreased in 31 countries, and rose in only 6. It decreased by more than 1 percentage point in 16 countries. The largest decreases were in Lithuania, the United States, Poland, Italy, Canada and Korea. The only increase over 1 percentage point was in New Zealand.

The gap between the OECD average tax wedge for the single average worker (34.6%) and the one-earner couple with children (24.4%) has widened by 0.7 percentage points since 2019, reflecting policy changes that provided additional support to families with children during the COVID-19 crisis.

The falls in country tax wedges for the single worker, the one-earner couple with two children, and the single parent resulted predominantly from changes in tax policy settings, although falling average wages also contributed in some countries. By contrast, increases in the tax wedge were almost all driven by rising average wages, offset only slightly by policy changes.

Of the ten countries where specific COVID-19 measures affected the indicators, support was primarily delivered through enhanced or one-off cash benefits, with a focus on supporting families with children.

The report shows that labour taxation continues to vary considerably across the OECD, with the tax wedge on the average single worker ranging from zero in Colombia to 51.5% in Belgium.

Further information and individual country notes: https://www.oecd.org/tax/taxing-wages-20725124.htm.

Contacts:

David Bradbury, Head of the OECD’s Tax Policy and Statistics division | David.Bradbury[at]oecd.org

Lawrence Speer | Lawrence.Speer[at]oecd.org in the OECD Media Office | news.contact[at]oecd.org

Compliments of the OECD.

The post OECD | Labour market disruption & COVID-19 support measures contribute to widespread falls in taxes on wages in 2020 first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.

Universal, accessible, timely and free-of-charge testing needed across the EU

EU COVID-19 certificates are not travel documents

Member states should not impose quarantines/tests on certificate holders

On Thursday, Parliament adopted its negotiating position on the proposal for a certificate to reaffirm the right to free movement in Europe during the pandemic.

MEPs agreed that the new “EU COVID-19 certificate” – instead of Digital Green Certificate, as proposed by the Commission – should be in place for 12 months and not longer.

The document, which may be in digital or paper format, will attest that a person has been vaccinated against coronavirus or, alternatively, that they have a recent negative test result or have recovered from the infection. However, EU COVID-19 certificates will neither serve as travel document nor become a precondition to exercise the right to free movement, say MEPs.

The legislative proposal covering EU nationals was approved with 540 votes to 119 and 31 abstentions, while the one on third-country nationals passed with 540 votes to 80 and 70 abstentions. The vote took place on Wednesday, with results announced on Thursday morning. Both Parliament and Council are now ready to begin negotiations. The aim is to reach an agreement ahead of the summer tourist season.

No additional travel restrictions and free COVID-19 tests

Holders of an EU COVID-19 certificate should not be subject to additional travel restrictions, such as quarantine, self-isolation or testing, according to the Parliament. MEPs also stress that, in order to avoid discrimination against those not vaccinated and for economic reasons, EU countries should “ensure universal, accessible, timely and free of charge testing”.

Compatible with national initiatives

Parliament wants to ensure that the EU certificate works alongside any initiative set up by the member states, which should also respect the same common legal framework.

Member states must accept vaccination certificates issued in other member states for persons inoculated with a vaccine authorised for use in the EU by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (currently Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, AstraZeneca and Janssen), MEPs say. It will be up to the member states to decide whether they also accept vaccination certificates issued in other member states for vaccines listed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) for emergency use.

Data protection safeguards

The certificates will be verified to prevent fraud and forgery, as will the authenticity of the electronic seals included in the document. Personal data obtained from the certificates cannot be stored in destination member states and there will be no central database established at EU level. The list of entities that will process and receive data will be public so that citizens can exercise their data protection rights under the General Data Protection Regulation.

Affordable vaccines allocated globally

Finally, MEPs underline that COVID-19 vaccines need to be produced at scale, priced affordably and allocated globally. They also voice concern about the serious problems caused by companies not complying with production and delivery schedules.

Quote

Following the vote in plenary, Juan Fernando López Aguilar (S&D, ES), Chair of the Civil Liberties Committee and rapporteur, said: “We need to put in place the EU COVID-19 Certificate to re-establish people’s confidence in Schengen while we continue to fight against the pandemic. Member states must coordinate their response in a safe manner and ensure the free movement of citizens within the EU. Vaccines and tests must be accessible and free for all citizens. Member states should not introduce further restrictions once the certificate is in force.”

Compliments of the European Parliament.

The post EU COVID-19 certificate must facilitate free movement without discrimination first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.

Euro area net saving decreased to €508 billion in four quarters to fourth quarter of 2020, from €549 billion one quarter earlier

Household debt-to-income ratio increased to 96.3% in fourth quarter of 2020 from 93.8% one year earlier

Non-financial corporations’ debt-to-GDP ratio (consolidated measure) at 84.0% in fourth quarter of 2020, up from 76.8% one year earlier

Total euro area economy

Euro area net saving decreased to €508 billion (5.6% of euro area net disposable income) in 2020 compared with €549 billion in the four quarters to the previous quarter. Euro area net non-financial investment decreased to €274 billion (3.0% of net disposable income), due to decreased investment by non-financial corporations, and to a lesser extent households, while net investment by financial corporations and government slightly increased.

Euro area net lending to the rest of the world increased to €243 billion (from €225 billion previously) reflecting net non-financial investment declining more than net saving. Net lending of non-financial corporations increased from €62 billion to €134 billion (1.5% of net disposable income), that of financial corporations rose from €84 billion to €109 billion (1.2% of net disposable income) and net lending by households increased from €684 billion to €821 billion (9.1% of net disposable income). The increase in net lending by the total private sector was largely offset by an increase in net borrowing by the government sector (-9.1% of net disposable income, after -6.6% previously).

Chart 1. Euro area saving, investment and net lending to the rest of the world

(EUR billions, four-quarter sums)

* Net saving minus net capital transfers to the rest of the world (equals change in net worth due to transactions).

Households

The annual growth rate of household financial investment increased to 4.1% in the fourth quarter of 2020, from 3.6% in the previous quarter. Investment in currency and deposits as well as in life insurance and pension schemes were the main contributors to this acceleration, while investment in shares and other equity grew at a broadly unchanged rate.

Households were net buyers of listed shares issued by all resident sectors and the rest of the world. Net purchases of listed shares issued by non-financial corporations grew at a broadly unchanged rate (5.6%), while net purchases of listed shares issued by the rest of the world accelerated (18.3% from 13.6% previously). Households continued to sell debt securities (in net terms) issued by all resident sectors and the rest of the world (see Table 1 below and Table 2.2. in the Annex).

Table 1. Financial investment and financing of households, main items

(annual growth rates)

Financial transactions

2019 Q4

2020 Q1

2020 Q2

2020 Q3

2020 Q4

Financial investment*

2.6

2.5

3.2

3.6

4.1

Currency and deposits

5.1

5.2

6.4

6.9

7.9

Debt securities

-10.8

-13.1

-10.8

-6.1

-7.6

Shares and other equity

0.3

1.0

1.9

2.3

2.2

Life insurance and pension schemes

2.7

2.0

1.7

1.4

1.8

Financing**

4.1

3.5

3.2

3.2

2.9

Loans

3.6

3.3

3.0

3.1

3.1

* Items not shown include: loans granted, prepayments of insurance premiums and reserves for outstanding claims and other accounts receivable.

** Items not shown include: financial derivatives’ net liabilities, pension schemes and other accounts payable.

Chart 2 below shows the stock of selected financial assets held by households (in dark blue) vis-à-vis counterpart sectors.[1] At the end of 2020, households’ financial assets with a counterpart sector breakdown were mostly liabilities of financial intermediaries such as MFIs (38% of households’ financial assets), insurance corporations (27%), pension funds (13%) and investment funds (12%). Direct holdings of financial assets issued by non-financial corporations (6%), government (1%) and the rest of the world (2%), e.g. in the form of listed shares and debt securities, represented much lower proportions of households’ financial assets.

Chart 2. Households’ financial assets by counterpart sector; selected financial instruments*

(2020 end of period stocks)

* Financial instruments for which the counterpart sector breakdown is available: deposits, loans, debt securities, listed shares and investment fund shares/units, as well as insurance, pension and standardised guarantee schemes (F.6). The counterpart sector breakdown for F.6 is estimated (See methodological note: Extension of the who-to-whom presentation to insurance and pension assets).

The household debt-to-income ratio[2] increased to 96.3% in the fourth quarter of 2020 from 93.8% in the fourth quarter of 2019, as disposable income grew slower than the outstanding amount of loans to households. The household debt-to-GDP ratio rose to 62.7% in the fourth quarter of 2020 from 57.8% in the fourth quarter of 2019 (see Chart 3), as debt increased and GDP declined.

Chart 3. Debt ratios of households and non-financial corporations

(debt as a percentage of GDP)

* Outstanding amount of loans, debt securities, trade credits and pension scheme liabilities.

** Outstanding amount of loans and debt securities, excluding debt positions between non-financial corporations.

***Outstanding amount of loan liabilities.

Non-financial corporations

In the fourth quarter of 2020, the annual growth of financing of non-financial corporations stood at an unchanged rate of 1.9% compared with the previous quarter. Financing by loans from financial corporations other than MFIs accelerated, while financing by intercompany loans, debt securities, shares and other equity decelerated. Loans from MFIs remained broadly unchanged. Trade credits declined, though at a lower rate (see Table 2 below and Table 3.2 in the Annex).

Non-financial corporations’ debt-to-GDP ratio (consolidated measure) increased to 84.0% in the fourth quarter of 2020, from 76.8% in the fourth quarter of 2019; the non-consolidated, wider debt measure increased to 147.6% from 136.8% (see Chart 3). The increases in these ratios were due to an increase in the debt of NFCs and a decline in GDP over this period.

Table 2. Financial investment and financing of non-financial corporations, main items

(annual growth rates)

Financial transactions

2019 Q4

2020 Q1

2020 Q2

2020 Q3

2020 Q4

Financing*

1.9

2.1

1.8

1.9

1.9

Debt securities

6.1

4.3

10.4

9.8

9.5

Loans

2.0

3.4

3.3

3.0

3.4

Shares and other equity

1.4

1.2

1.1

1.3

1.0

Trade credits and advances

2.0

1.0

-4.9

-2.8

-0.5

Financial investment**

2.3

2.3

2.5

2.9

3.1

Currency and deposits

5.8

9.7

18.3

20.1

18.7

Debt securities

-8.9

-2.3

9.2

6.8

7.9

Loans

1.6

0.5

-0.3

0.0

0.2

Shares and other equity

2.1

2.1

2.1

2.1

1.7

* Items not shown include: pension schemes, other accounts payable, financial derivatives’ net liabilities and deposits.

** Items not shown include: other accounts receivable and prepayments of insurance premiums and reserves for outstanding claims.

Chart 4 below shows the non-financial corporations’ debt (in dark blue) vis-à-vis counterpart sectors. At the end of 2020, the non-financial corporations’ debt in the form of loans and debt securities was held primarily by MFIs (36%), other non-financial corporations (27%), the rest of the world (15%) and other financial institutions (12%).

Chart 4. The main components of NFC debt (loans and debt securities) by counterpart sector

(2020 end of period stocks)

For queries, please use the Statistical information request form.

Notes

These data come from a second release of quarterly euro area sector accounts from the European Central Bank (ECB) and Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union. This release incorporates revisions and completed data for all sectors compared with the first quarterly release on “Euro area households and non-financial corporations” of 9 April 2021.

The debt-to-GDP (or debt-to-income) ratios are calculated as the outstanding amount of debt in the reference quarter divided by the sum of GDP (or income) in the four quarters to the reference quarter. The ratio of non-financial transactions (e.g. savings) as a percentage of income or GDP is calculated as sum of the four quarters to the reference quarter for both numerator and denominator.

The annual growth rate of non-financial transactions and of outstanding assets and liabilities (stocks) is calculated as the percentage change between the value for a given quarter and that value recorded four quarters earlier. The annual growth rates used for financial transactions refer to the total value of transactions during the year in relation to the outstanding stock a year before.

The next release of the Household Sector Report containing results for the euro area and all EU countries is scheduled for 11 May 2021.

Hyperlinks in the main body of the statistical release lead to data that may change with subsequent releases as a result of revisions. Figures shown in annex tables are a snapshot of the data as at the time of the current release.

The production of quarterly financial accounts (QFA) may have been affected by the COVID-19 crisis. More information on the potential impact on QFA can be found here.

Compliments of the European Central bank.

The post ECB | Euro area economic and financial developments by institutional sector: fourth quarter of 2020 first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.

The Council has today adopted a decision on the conclusion of the EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement and the security of information agreement. This is the last step for the EU in the ratification of the agreements.

The UK will now be notified of the finalisation of the internal EU procedures. Following this, the agreements and accompanying texts will be published in the Official Journal of the EU before the end of the month. On 1 May 2021, both agreements will enter into force.

Today we open a new chapter in our relations with the UK. The conclusion of the trade and cooperation agreement will give legal certainty to the new EU-UK relationship, in the interests of citizens and business on both sides of the channel. We value the UK as a good neighbour, an old ally and an important partner.

Ana Paula Zacarias, Secretary of State for European Affairs of Portugal

Background

Negotiators reached an agreement on an EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement and a security of information agreement on 24 December 2020.

On 29 December 2020, the Council adopted the decision on the signing of the EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement and a security of information agreement and on their provisional application as of 1 January 2021. The agreements were then signed by the two parties on 30 December 2020. The agreements have been provisionally applied since 1 January 2021.

The agreements provided for a time-limited provisional application until the end of February, unless a later date was agreed by the parties. On 23 February, the EU-UK Partnership Council decided, at the EU’s request, to extend the provisional application until 30 April 2021 to allow sufficient time to complete the legal-linguistic revision of the agreement in all 24 languages. The authentication of all 24 language versions of the agreement was finalised on 21 April.

On 26 February 2021, the Council requested the European Parliament’s consent to its decision on the conclusion of the agreements, which the European Parliament gave on 27 April.

Council decision on the conclusion of the EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement and the security of information agreement

EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement

EU-UK security of information agreement

Declarations in relation to the trade and cooperation agreement and the security of information agreement

EU-UK negotiations on the future relationship (background)

Compliments of the Council of the European Union.

The post EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement: Council adopts decision on conclusion first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.

Keynote speech by Frank Elderson, Vice-Chair of the Supervisory Board and Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the conference on “The Role of Banks in Greening Our Economies” organised by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and Hrvatska narodna banka |

It is a great honour for me to be with you today to discuss the role of banks in greening the economy. And I am very happy to delve into the topic of climate change at an event co-organised by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) – an institution whose own work remarkably exemplifies what international cooperation can achieve in supporting the greening of the economy. Your commitment to meeting the goals set under the Paris Agreement is outstanding. It offers great inspiration to all of us in European institutions who are just as adamant about doing the same. As many of you know, climate change considerations feature prominently in the ECB’s ongoing monetary policy strategy review. But today I will focus on how they will be taken into account by ECB Banking Supervision.

The challenge of climate change is daunting. This is certainly true for the consequences if climate change continues unabated, such as increased natural disasters and the loss of habitats and biodiversity. And it is also true for the transformation necessary to avoid these dire consequences. The OECD[1] estimates that global investments of USD 6.9 trillion every year are required until 2030. And that is just to keep us on track to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Investment will need to be considerably higher than this USD 6.9 trillion figure if we are to live up to our commitment under the Paris Agreement of limiting the increase in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees. To put this number into perspective: we are talking somewhere around 8% percent of global GDP each year.

Europe’s financial system is largely bank-based, so banks are playing a pivotal role in greening the economy. But what is the supervisor’s role in this process? The ECB aims to ensure the safety and soundness of the banks we supervise. Climate change creates material risks for banks, so it is our job to ensure that the banks under our supervision address these risks adequately and proactively.

Regarding the risks emanating from climate change, our sole aim is to live up to our mandate. There is a knock-on effect of doing so, however, but it is a welcome one. By compelling banks to adequately assess and manage climate-related risks, we are, in effect, safeguarding the financing of the transition to a low-carbon economy as well. If banks proactively manage climate-related risks, they will not be blindsided by stranded assets, meaning that capital will be preserved and can be used to finance investments in the low-carbon transformation. And climate-related risks being adequately represented on banks’ balance sheets will contribute to these risks being appropriately priced. So if ECB Banking Supervision recognises the financial risks emanating from climate change, this will have a dual effect – it will compel banks to take these risks into account, which in turn will induce companies and households to factor them in as well. This alone will not fully internalise the damage caused by greenhouse gas emissions; other institutions are in charge of making sure of that. But it is an important piece of the puzzle.

The urgency to act – climate change is irreversible

The EU has committed to becoming carbon-neutral by 2050. The change that our economies need to undertake must be structural. We must reduce the use of fossil fuels as quickly as possible and move towards greener infrastructure that can support the global economy in a way that is sustainable and that protects our planet’s ecosystems and biodiversity.

Much has been made of the dip in carbon emissions that resulted from the economic shutdown in 2020 in many countries. But to reach the Paris target, every single year we need reductions in emissions that are greater than last year’s, and we need to bring about these reductions by ramping up the use of clean technologies, not by shutting down our economies. Unfortunately, even the too-small drop in emissions we saw last year seems set to be all but reversed in 2021. The International Energy Agency expects to see the second-biggest increase in carbon emissions in history this year, eradicating 80% of the 2020 reductions.[2] The good news is that 2021 may also provide just the kind of momentum we need to tackle climate change effectively. As the European Union and national governments start making large investments to pave the way for recovery, it is crucial that those funds are channelled towards activities that support our transition to a greener economy.

I will now discuss ECB Banking Supervision’s latest initiatives to ensure that banks adequately manage climate-related risks. This is our mandate. As I said earlier, this will also have the positive knock-on effect of inducing banks, and thus companies and households, to factor in climate effects when allocating funds. And this will help accelerate the reduction of carbon emissions – all the way to zero by 2050 at the latest.

How ECB Banking Supervision is tackling climate risk

Climate risk can affect banks through different channels.

As I am sure many of you already know, the main risk drivers for banks are physical risks and transition risks. Physical risks include all those resulting from a changing climate, from more frequent extreme weather events and gradual changes in climate, to environmental degradation, such as air, water and land pollution, water stress, biodiversity loss and deforestation. For example, extreme weather events – which have been steadily increasing over recent decades[3] – can harm borrowers’ ability to repay their debts and thus make the loan portfolios of banks much riskier. These risks can be further heightened if extreme weather events also depreciate the value of the assets used as collateral in those loans.

Transition risks, on the other hand, include the financial losses that can directly or indirectly result from the process of adjusting to a low-carbon and more environmentally sustainable economy. This adjustment could be triggered by legislation, such as carbon pricing or the banning of carbon-intensive activities. Even independently from that, consumer preferences could shift towards goods and services that are more climate-friendly. An ECB initial assessment confirms that an abrupt transition to a low-carbon economy would have a severe impact on climate-sensitive economic sectors, with consequences for up to one-tenth of banking sector assets if the creditworthiness of the highest carbon emitting firms is reassessed, and affecting more than half of banking sector assets if entire economic sectors are reassessed.[4] And preliminary results from our ongoing climate stress test show that without further policy action, companies will face substantially rising costs from extreme weather events. This will greatly raise their probability of default.[5]

Both physical and transition risks will become increasingly material for banks in the coming years, and ECB Banking Supervision has identified climate change as one of the key risk drivers for the European banking sector. In line with this assessment, we are taking steps to increase our understanding of the impact of climate change from a financial perspective and to ensure that banks fully incorporate these risks into their processes and practices.

I will now go through the recent and ongoing climate-related initiatives related to our supervisory work.

The ECB Guide and climate-related disclosures

In November last year we published the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks.[6] It builds on the Guide for Supervisors[7] of the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), and communicates the ECB’s understanding of a prudent approach to managing such risks to banks, markets and the wider public, with the aim of raising banks’ awareness and preparedness for managing them. In our Guide, we outline our supervisory expectations for how climate and environmental risks should be embedded in all relevant bank processes, from banks’ risk management frameworks to their governance structures, risk appetite, business model and strategy, and, importantly, their reporting and disclosures.

Our ultimate goal is to cause banks to make sure their business strategies fully reflect the Paris Agreement – and there is one thing that will be key in getting us there: data. When it comes to tackling climate risk as a financial risk, data are what we are missing the most.

Recently, a Task Force on Climate-related Financial Risks that operates under the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision looked into the effects of physical and transition risks on banks. This task force, which I have the honour to co-chair with the Federal Reserve System’s Kevin Stiroh, concluded that climate-related risks can be captured in risk categories that are already used by financial institutions and reflected in the Basel Framework, for example credit risk, market risk, liquidity risk and operational risk. This is a key insight which saves us from inventing all kinds of new risk categories. The existing ones will do. However, the task force also concluded that we still need an enhanced toolbox that can better measure climate risks. This is why the ECB is encouraging banks to enhance both the quantity and the quality of their climate-related disclosures, and to become more transparent about their overall exposures to climate-related risks.

Banks are still in the early stages of incorporating climate change into their risk frameworks; risk identification and risk limits around climate-related goals do not yet actually feature in their risk management processes. This needs to change. Euro area banks need to drastically improve their capacity to manage climate-related and environmental risks and start acknowledging how these risks can drive others, including credit, market, operational and liquidity risks. Crucially, we have no need to await regulatory developments before formulating our expectations for the management of climate-related risks. They are firmly grounded on actual requirements and stem from the simple fact that climate-related risks are on the rise and need to be tackled seriously by the whole financial sector.

Incorporating climate-related risks into ongoing supervision and stress testing

This is why we have already asked banks to conduct a self-assessment against the supervisory expectations outlined in our Guide and draw up action plans for aligning their practices to them. The assessment covers 112 institutions, representing 99% of total assets under our direct supervision. All banks have already handed in their self-assessments and are now finalising their action plans. We are currently assessing banks’ submissions and will be challenging them in all of these areas. Where we see that banks are not managing their exposures to climate-related risks in an adequate manner, we can and will draw on the full supervisory toolkit at our disposal to correct that situation. Just as we do for any other material risk.

We have already started work on incorporating climate-related risks into our Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) methodology. This year the outcomes of these assessments will not be translated into quantitative capital requirements across the board, but we may impose qualitative or quantitative requirements on a case-by-case basis. We expect that the actions we are taking in 2021 will result in banks being adequately prepared for the full supervisory review which we will conduct in 2022.

Currently, the ECB is also carrying out a stress test to assess the impact of climate-related risks on the European banking sector over a 30-year horizon.[8] We will map projections of climate patterns and expected climate developments to the location of firms’ physical assets and estimate the impact that severe climate events would have on those assets and, consequently, on banks’ portfolios. Together with other central banks, we are developing joint climate stress test scenarios.

Besides allowing us to conduct an in-depth investigation into banks’ internal practices around climate risk stress testing for the first time ever, the stress test will help us catalogue the resilience of banks’ balance sheets to risks coming from climate change. Importantly, this exercise will push banks to strengthen the climate dimension of their risk management toolbox. Finally, the exercise will also dramatically increase the availability of data and shed light on our supervisory reporting needs around these types of risks. Given our current lack of data, this will greatly help us in charting the course forward.

This year’s climate stress test exercise is being conducted centrally by ECB staff, relying on the aforementioned datasets and models. This approach differs from that taken for the supervisory climate stress test, which has already been announced for 2022. Next year’s climate stress test of individual banks will instead rely on the banks’ self-assessment of their exposure to climate change risk and their readiness to address it. In stress test parlance: this year’s test is “top-down”, whereas next year’s is “bottom-up”.

As banks become better prepared to face the risks posed by climate change, they need to be led by people who are also better prepared to deal with these topics. When assessing the suitability of prospective members of the management body of banks, knowledge and experience of climate-related and environmental risks will be among the areas of general banking experience against which suitability will be assessed. Finally, we will seek to include an understanding of climate-related and environmental risks as a specific area of expertise within the collective suitability of a bank board.

An environmental risk that is intimately connected to climate change, but also constitutes a risk in itself, is the loss of biodiversity. In our Guide on climate-related and environmental risks we single out biodiversity loss as one of the drivers of both physical and transition risk.

It is becoming ever clearer that beyond climate-related risks, biodiversity loss could also be a source of material financial risks.[9] More research needs to be done.[10] At the ECB, we will follow these developments closely – and we encourage banks to do the same.

Integrating international networks and European initiatives

Much like the EBRD, the ECB is also part of global initiatives which promote international cooperation on joint solutions for climate change.

Most prominently, the ECB is a member of the NGFS. Launched in 2017, this network, which I am honoured to have chaired from the beginning, brings together central banks and financial supervisors to track supervisory developments and develop climate scenarios for central banks and supervisors. The network also explores paths to scale up green finance and monitor its market dynamics, thereby bridging data gaps and coordinating research in the fields of climate-related and environmental risks. I am happy to mention that the NGFS has just welcomed its ninetieth member.

The Basel Committee’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Risks will continue working on the further integration of climate-related financial risks into the Basel framework and expectations. To help address the remaining challenges in terms of measuring climate-related financial risks, the ECB is working closely with the European Banking Authority (EBA) on the management and supervision of ESG risks. We have also provided our input to the European Commission’s EU taxonomy for sustainable activities and its non-financial reporting directive (NFRD), which requires large European companies to disclose information on their policies in areas such as environmental protection and social responsibility. In particular, the ECB supports the ongoing work by the Basel Committee and the Financial Stability Board (FSB) on effective and consistent regulatory and supervisory approaches for dealing with climate risks.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

When dealing with the risks arising from climate change, we must be forward-looking, comprehensive and strategic. But we must also be swift. Emissions need to fall at a much faster pace than seen so far if we want to avert irreversible damage.

I am hopeful that the lessons we draw from the COVID-19 crisis may end up helping to tackle climate risks, not least by showing us that when faced with global challenges, we need to – and indeed can – respond with joint solutions. To reduce carbon emissions all the way to zero by 2050, joint action at the global level is just as vital.

Today I have listed some of the ways in which, through our supervisory action and as part of international networks, the ECB is compelling banks to account for climate change – when managing risks, selecting their board members and devising stress scenarios.

Climate-related risks show up in the already existing risk categories – as such, we will treat them with the same rigour, toughness and importance as we treat other material risks. And we expect banks to do the same. Urgent action is not an option; it is an imperative.

Compliments of the European Central Bank.

The post ECB Speech | All the way to zero: guiding banks towards a carbon-neutral Europe first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.

Political groups strongly welcome the agreement

Parliament must have a say in the implementation of the agreement

Agreement will enter into force on 1 May after Council conclusion

Parliament voted with a large majority in favour of granting its consent to the agreement setting the rules of the future EU-UK relationship.

The consent decision was adopted by 660 votes for, five against and 32 abstentions, while the accompanying resolution, setting out Parliament’s evaluation of and expectations from the deal, passed by 578 votes, with 51 against and 68 abstentions. The vote took place on Tuesday, with results announced on Wednesday.

On 24 December 2020, EU and UK negotiators had agreed on the Trade and Cooperation Agreement establishing the terms for future EU-UK cooperation. To minimise disruption, the agreement has been provisionally applied since 1 January 2021. Parliament’s consent is necessary for the agreement to enter into force permanently before its lapse on 30 April 2021.

Departure is “historic mistake”, but deal is welcome

In the resolution prepared by the UK Coordination Group and the Conference of Presidents, Parliament strongly welcomes the conclusion of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement that limits the negative consequences of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, which it considers a “historic mistake” as no third country can enjoy the same benefits as an EU member.

The zero quotas and zero tariffs trade agreement between the EU and the UK are viewed positively by MEPs, and guarantees on fair competition rules could serve as a model for future trade agreements, MEPs add. Parliament agrees with provisions on, among others, fisheries, consumers, air traffic and energy.

However, MEPs regret that the UK did not want the agreement to extend to foreign, security and development policies and did not want to participate in the Erasmus+ student exchange programme.

Peace on the island of Ireland

Pointing to preserving peace on the island of Ireland as one of Parliament’s main goals in agreeing the future relationship, MEPs condemn the UK’s recent unilateral actions that are in breach of the Withdrawal Agreement. They call on the UK government “to act in good faith and fully implement the terms of the agreements which it has signed”, including the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland, and apply them based on a timetable jointly set up with the European Commission.

Parliament to be involved in monitoring

MEPs underline that Parliament must play a full role in monitoring how the agreement is applied, including by being involved in unilateral EU actions under the agreement and having its views taken into account.

Quotes

“The EU and the UK have created the basis for a relationship among equals. Most importantly, today is a beginning, not the end. We agreed in many important areas, such as securing mutual market access and building a good relationship on trade. Much work remains on foreign policy and educational exchange programmes. For citizens’ interests to be represented, Parliament must be closely involved. Only a partnership in which both sides stick to their commitments has a future,” said Andreas Schieder (S&D, AT), rapporteur for the Committee on Foreign Affairs.

“Ratification of the agreement is not a vote of blind confidence in the UK Government’s intention to implement our agreements in good faith. Rather, it is an EU insurance policy against further unilateral deviations from what was jointly agreed. Parliament will remain vigilant. Let’s now convene the Parliamentary Partnership Assembly to continue building bridges across the Channel,“ said Christophe Hansen (EPP, LU), rapporteur for the Committee on International Trade.

Next steps

With Parliament’s consent, the agreement will enter into force once Council has concluded it by 30 April.

Compliments of the European Parliament.

The post EU Parliament formally approves EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement first appeared on European American Chamber of Commerce New York [EACCNY] | Your Partner for Transatlantic Business Resources.