You may have heard about Pillar Two, and you may have also heard that the Netherlands, as the first country in the EU, published Pillar Two draft legislation on October 24th, 2022. This draft will now be updated following a round of public consultation, after which the amended draft legislation will be presented to the Dutch Parliament, with the aim to get it implemented and effective by the start of 2024. Now you may be wondering what this is all about, if and when this is actually going to happen, and whether you should care – below we summarize, visualize & cover some FAQs on Pillar Two general systematics and the Dutch draft rules.

FAQs: Pillar Two in general

What is Pillar Two again?

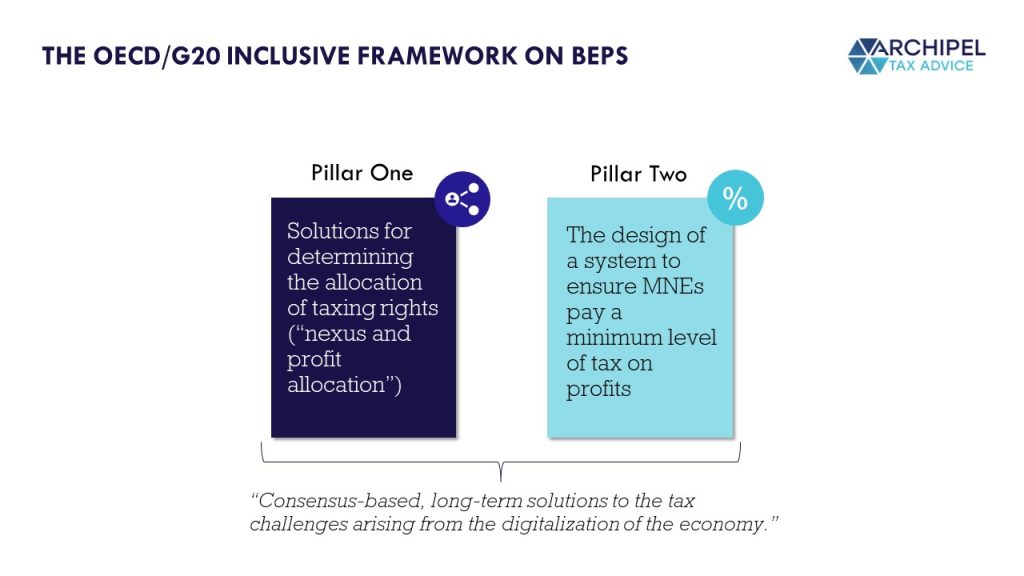

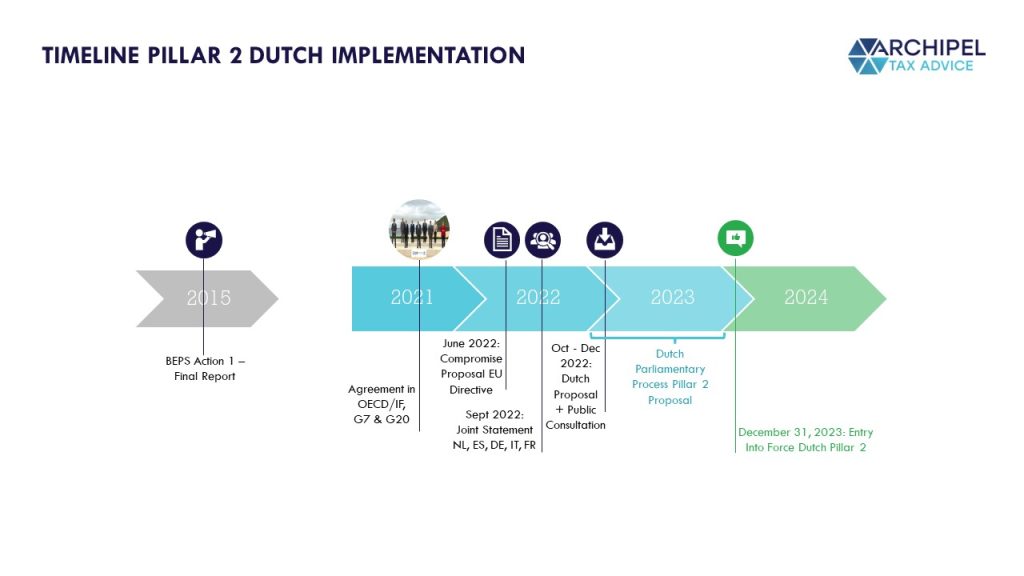

Pillar Two is part of a two-pillar solution resulting from the OECD’s BEPS Action 1 (set back in 2015), calling to address the tax challenges arising from the digitalization of the economy. Per October 2021, over 135 jurisdictions have signed on to the statement on the Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy, to reform the international tax system in light of this ongoing increasing digitalization.

In short, Pillar One aims to realign taxing rights towards ‘market jurisdictions’ where MNEs lack a physical presence, and Pillar Two aims to ensure that a minimum level of tax is paid, addressing the challenges of the digitalizing economy where the relative importance of intangible assets as profit drivers may still leave room for profit shifting planning.

What are the basics of Pillar Two?

To put it in a nutshell (with reference to the following questions for further details):

What is Pillar Two trying to achieve?

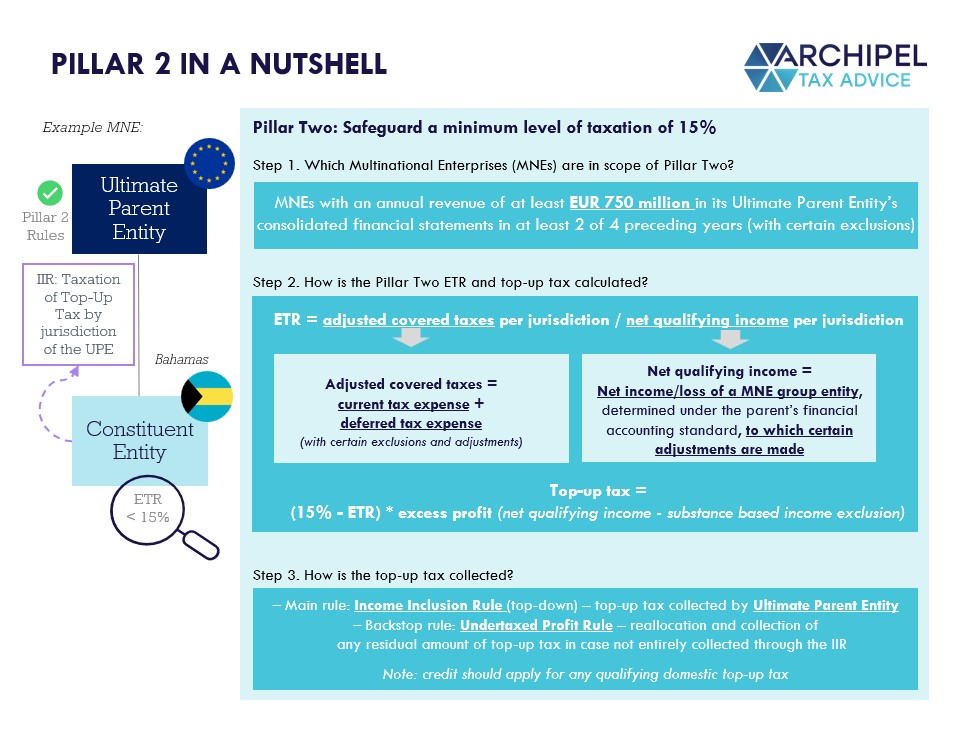

Pillar Two is designed to ensure that MNEs pay a minimal level of tax in every jurisdiction in which they have a taxable presence, therewith also lowering the incentive for MNEs to ‘shift’ profits to lower tax jurisdictions, for example through moving IP or other tangible assets to those jurisdictions. The minimum level of tax is set at a rate of 15% over a ‘common’ tax base determined based on the Pillar Two rules.

Where do we stand today?

While originally presented as a combined ‘two-pillar solution’, the implementation of each Pillar is now following a different track and it seems likely, at least in a number of jurisdictions, that implementation will take place separately. In December last year (2021), the OECD/IF released its first draft of the Pillar Two ‘Model Rules’, closely followed by the European Commission releasing its (largely similar) draft Pillar Two Directive. These drafts, once finalized, are meant to serve as a template for the implementation into domestic law.

Although Pillar Two was initially back on the agenda for the last Ecofin meeting on December 6th, 2022, the draft EU Directive has still not been adopted, as the required unilateral agreement by all EU Member States has not yet been reached. Recently, however (September 2022), a joint statement was issued by the governments of France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain, reconfirming their commitment to the implementation of the global minimum tax (essentially Pillar Two). Following that statement, as mentioned, the Netherlands is now the first of these five to have published its draft Pillar Two legislation, with intended implementation for financial years starting on or after 12/31/2023.

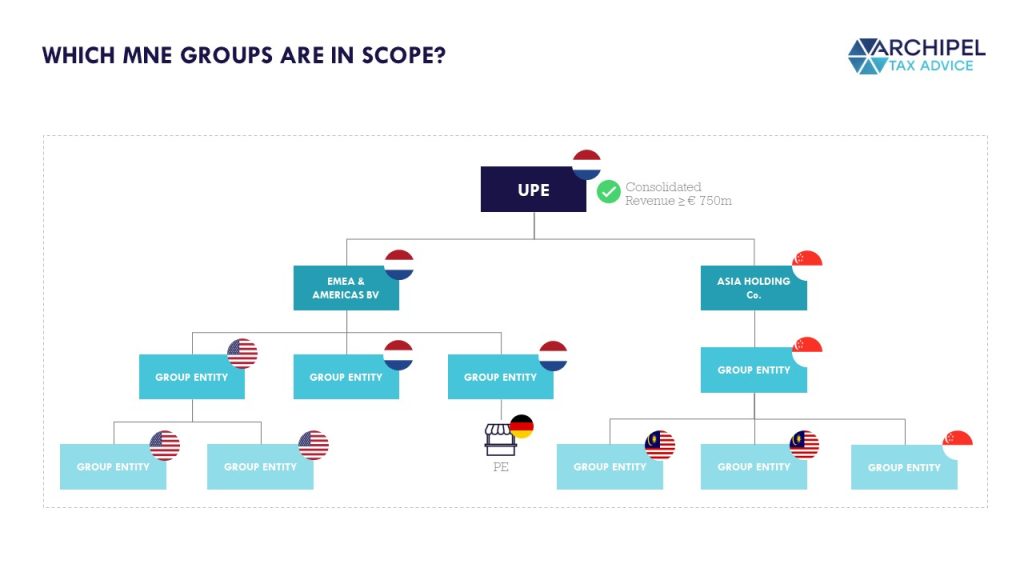

Will it apply to me?

The Pillar Two rules apply to entities that are part of an MNE Group with an annual revenue of at least EUR 750 Million based on an Accepted Financial Accounting Standard (similar to the threshold for the existing Country-by-Country Reporting or ‘CbCR’ rules). To be in scope, the Ultimate Parent Entity (‘UPE’) of the MNE Group must meet the revenue threshold on a consolidated basis for at least two of the four years immediately preceding the relevant fiscal year. The UPE is described as an entity that has a Controlling Interest -directly or indirectly- in any other Entity (and is itself not owned -directly or indirectly- by another entity with a Controlling Interest in it). A Controlling Interest is a recurring term in the Pillar Two rules and is defined as an Ownership Interest in an Entity for which the interest holder is -or would have been- required to consolidate the assets, liabilities, income, expenses, and cashflows of the Entity. In addition, a Main Entity is deemed to have the Controlling Interest in its Permanent Establishments, based on which the Model Rules also apply to companies with Permanent Establishments in one or more jurisdictions. Certain entities, such as NGOs, Investment Funds, and Pension Funds, are excluded from the Pillar Two rules.

How is the ETR for Pillar Two calculated?

The ETR of an MNE under Pillar Two rules is determined by dividing the amount of ‘Covered Taxes’ by the amount of income as determined under the Pillar Two rules. In short, Covered Taxes include any tax on an entity’s income or profits (including a tax on distributed profits) and include any taxes imposed instead of a generally applicable income tax. Covered taxes also include taxes on retained earnings and corporate equity. The MNE’s income is calculated starting with the standalone financials of group entities (or permanent establishments) determined under the same accounting standards as the consolidated financial statements at UPE level, i.e. the Financial Accounting Net Income before consolidation to eliminate intra-group transactions. Subsequently, certain adjustments (some mandatory, some elective) are to be made in order to align the determination of the income base better with common (tax) standards.

Once the Covered Taxes, as well as the (adjusted) income (or loss), has been determined under the Pillar Two rules, these amounts are grouped for all in-scope entities (or permanent establishments) within the same jurisdiction (with certain consolidation eliminations for income/loss of entities in tax groups in the same jurisdiction) to eventually determine the Pillar Two ETR for that jurisdiction. Note that when calculating the ETR, the taxable income for a jurisdiction may be lowered with a substance-based carve-out (a percentage of payroll costs and tangible asset value) to allow for a fixed return for ‘real economic activity’ to be out of scope.

Finally, the amount of Top-Up Tax for each group entity is equal to the difference between the ETR and the minimum ETR under the Pillar Two rules, multiplied by the adjusted income of the group entity.

So why can’t I just use my existing ETR calculations?

Although these can be a good starting point, the ETR for purposes of the Pillar Two rules may be different in some cases as it is calculated based on a new set of rules determining which income (or loss) and which taxes should be taken into account as described above.

To get into the details a bit – the rules based on which we determine what goes into the ETR calculation in terms of taxes and income for Pillar Two purposes are different from the rules used for the existing ETR calculations. And although there are quite some similarities, there can also be some differences that could lead to a different ETR for Pillar Two, for example:

- A different starting point is used for determining the taxable income – i.e. the commercial financial numbers for each in-scope entity (or permanent establishment) as used in the preparation of the UPE’s consolidated financial statements (before consolidation adjustments to eliminate intra-group transactions).

- Different adjustments may be made to get from commercial income to (Pillar Two) taxable income – examples include net tax expense, dividends and capital gains from certain subsidiaries, arm’s length adjustments, consolidation eliminations for entities in tax groups in the same jurisdiction, exclusions for income derived from shipping, etc. Although some of these look similar to what we’re used to, some may differ or apply under different conditions. Moreover, certain adjustments that are made for local tax purposes today, like the innovation box regime in the Netherlands, do not exist under the Pillar Two rules.

- Deferred taxes are subject to certain adjustments under the Pillar Two rules – for example, deferred tax expenses are calculated at a maximum rate of 15%, and so-called recapture rules could take back the deferred tax -with some exceptions- if the deferred amount is not paid within five subsequent fiscal years.

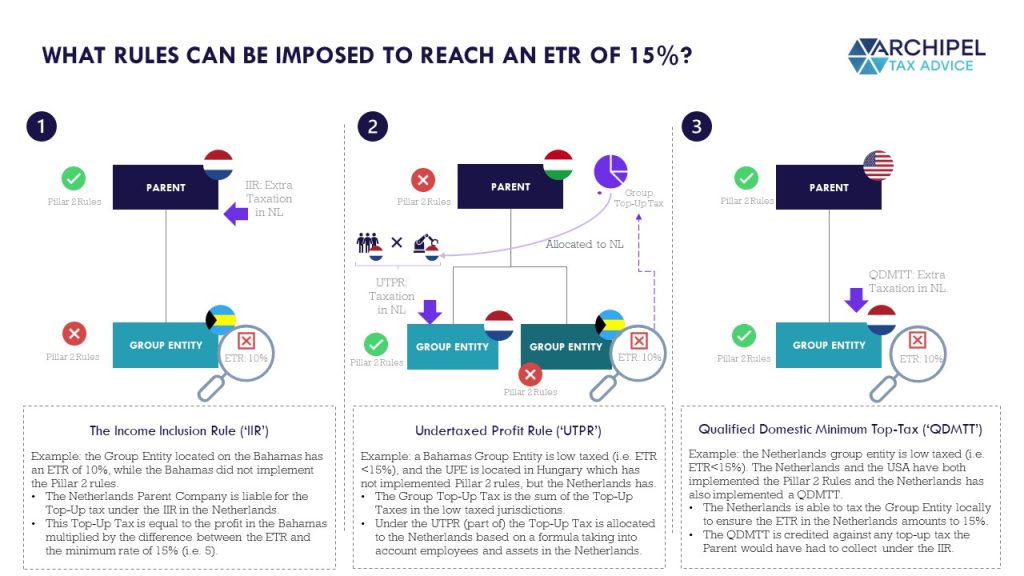

If there is any top-up tax due, how and where will this be collected?

The key systematics of Pillar Two have been designed to include a main ‘top-down’ rule, the Income Inclusion Rule (‘IIR’), and a backstop rule, the Undertaxed Profit Rule (‘UTPR’). The IIR imposes a Top-Up Tax on the UPE with respect to low-taxed income (below 15%) of a foreign subsidiary or permanent establishment (comparable to a sort of CFC rule). The UTPR acts as a backstop rule to collect any top-up tax that is not collected under the IIR, and is effectuated through the denial of deductions (or other profit adjustments) applied by the (lower-tier) group entities in other jurisdictions that have implemented the UTPR (divided based on the number of employees and tangible asset value in the UTPR jurisdictions).

Next to the IIR and UTPR, the OECD and EU Pillar Two draft rules however also leave room for so-called Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Taxes (‘QDMTT’) which, if imposed, lower the top-up tax to be collected under the IIR and UTPR. As this QDMTT allows jurisdictions to collect the additional tax determined under Pillar Two rules themselves instead of potentially having other jurisdictions do so under the IIR or UTPR, it is expected that a lot of jurisdictions will introduce such a domestic tax, meaning that the collection of the top-up tax will, in that case, happen in the jurisdiction where the Pillar Two ETR is below 15%. Refer to the below visual for some simplified examples of how the IIR, UTPR and QDMTT could apply.

Looking at these systematics, it is rather crucial that the rules are implemented consistently across jurisdictions, producing the same overall result to ensure that the MNE Group is subject to a minimum level of taxation in each jurisdiction without exposing it to the risk of double taxation. Although the OECD and EU drafts aim to facilitate such consistency, local implementations may still differ in terms of exact rules or interpretation/application thereof.

FAQs: the Dutch Pillar Two draft legislation

What is the current status of the implementation of the rules?

Following the publication of the draft rules and the closing of the public consultation round, the draft proposal will now be updated and then presented to the Dutch Parliament, where the legislation will be discussed in both Houses. The rules are then intended to be finalized and implemented during the course of 2023 to start applying for financial years starting on or after December 31, 2023 (and December 31, 2024 for the UTPR).

What about the proposed EU Pillar Two Directive?

The Dutch draft legislation is meant to implement the proposed EU Pillar Two Directive (specifically the compromise text of June 16, 2022). Even though agreement at EU level has not yet been reached, the Dutch government still favors a common EU approach. The joint statement brought out together with France, Germany, Italy and Spain in September this year reconfirms the wish to reach agreement at EU level and therewith the commitment of the Netherlands to implement the Directive timely. The Dutch government indicated the draft legislation can form the basis for definitive proposed legislation, whereby EU developments are monitored closely.

How will the draft legislation be incorporated into the Dutch tax legislation?

To implement the rules in its domestic legislation, the Netherlands has chosen to create a separate tax act in addition to its current Corporate Income Tax Act (‘CITA’). The reason for having a new and separate act is primarily to avoid adding complexity to the current CITA.

Did the Netherlands opt for the QDMTT?

The Dutch draft legislation includes the optional QDMTT. The QDMTT aims to ensure that the Netherlands will be able to collect the Top-Up Tax of Dutch-based low-taxed entities (or permanent establishments) locally in the scenario the parent entity is not located in the Netherlands. If the Dutch domestic rules qualify as a QDMTT, a UPE located in another jurisdiction is, in principle, obliged to give a credit for the top-up tax collected under the Dutch QDMTT (we refer to the explanation above).

What is considered an MNE group?

An MNE group is a group of entities that are connected by ownership or control. The Pillar Two rules are linked to the group concept in the accounting standard rules as applied at UPE level when drawing up the consolidated annual accounts. The second form of an MNE group could be an entity with one or more permanent establishments – provided that the entity is not already part of an MNE group.

What if the company only has a presence in one jurisdiction?

In that case, the company can still qualify as a large-scale domestic group, which is in principle also in-scope of the Pillar Two rules.

What is considered to be a group entity?

The Dutch draft legislation identifies three types of group entities:

- An entity that is part of an MNE group;

- An entity that is part of a large-scale domestic group; and

- A permanent establishment of an entity that is part of an MNE group.

Is a permanent establishment considered an entity?

A permanent establishment is treated as a separate group entity for purposes of the Dutch Pillar Two rules. This ensures that the income derived by the permanent establishment is not included in the calculation of the ETR in the jurisdiction of its Parent.

Must the entity have a legal personality?

An ‘entity’ is treated as such if it has legal personality and/or if it prepares financial statements, which is also the case for partnerships or trusts. It is, therefore, not necessarily required to have legal personality. Individuals do not fall under the definition of ‘entity’.

Are dividends (or other benefits) derived from subsidiaries included as income for the ETR calculation?

The rules deviate from the existing rules of the Dutch participation exemption in the CITA. Where the Dutch participation exemption generally excludes dividends and capital gains derived from qualifying subsidiaries in which ownership interests of 5% or more are held without a minimum holding period, the draft Dutch Pillar Two rules only allow for the exclusion of dividends and other income derived from a subsidiary if the ownership interest in that subsidiary is 10% or more and/or if the subsidiary has been held for at least a year. Based thereon, the taxable income under the Dutch CITA could look different from the income under the Dutch Pillar Two rules.

Another example of where the rules deviate is in relation to liquidation losses, which can under circumstances be taken into account when determining the taxable income under the Dutch CITA, while such losses are not taken into account under the Dutch Pillar Two rules.

Do the Pillar Two rules impact the application of the Dutch Innovation Box?

The innovation box effectively lowers the CIT rate from 25.8% to 9% for income derived from qualifying innovative activities. As a result, companies applying the innovation box may have a lower ETR in comparison to other companies. Although the Pillar Two rules will not impact the application of the Dutch innovation box as such, the effectiveness may be impacted by the Pillar Two rules if these would result in additional taxation up to the 15% minimum tax level. It is, however, expected that in most cases, the application of the Innovation Box will not result in an overall ETR of less than 15% (on a blended basis, seeing as the Dutch headline rate is 25.8% and generally only part of the revenue of a company is attributable to the innovation box). Therefore, it is not expected that this will impact many Dutch-based companies according to the explanatory statements to the Dutch draft Pillar Two legislation.

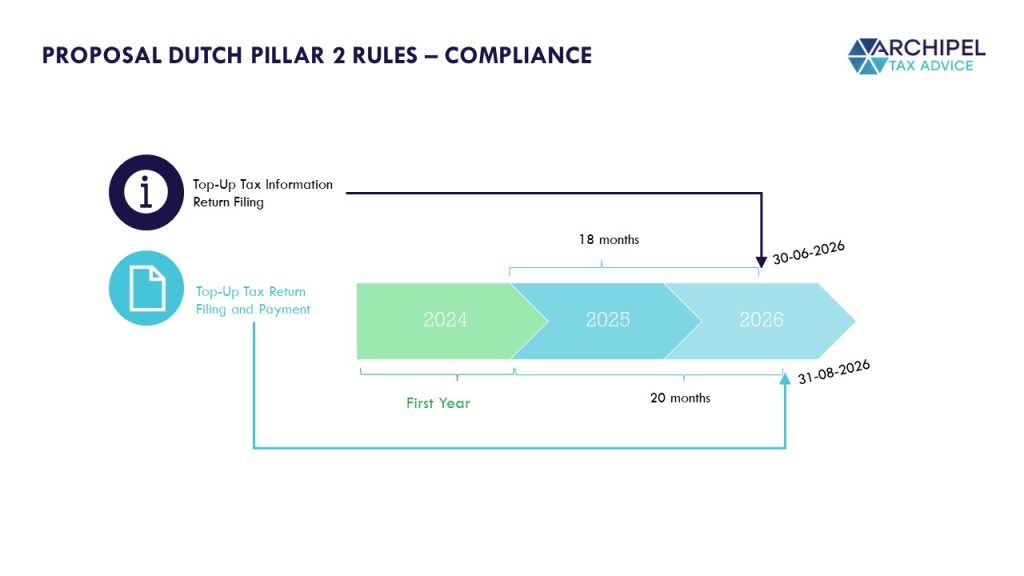

What will the compliance process of the new Pillar Two Act look like?

It is proposed that the in-scope Dutch-based UPE or group entity of an MNE should file a Pillar Two specific top-up tax information return separate from the actual top-up tax return. This top-up tax information return should contain the calculation of the top-up tax and the distribution thereof across the jurisdictions. Following the initial year in which the Pillar Two rules take effect in the Netherlands (likely 2024), a Netherlands-based UPE or MNE group entity has 18 months to file the top-up tax information return. Two months later, the consequent Pillar Two top-up tax return and payment term end, i.e. 20 months following the end of the initial year. In the second year (likely 2025), the information return should be filed within 15 months after the end of the second year, and the top-up tax return and payment term end 17 months following the end of the second year. As such, there is a bit more runway for taxpayers to allow for sufficient time to process the complex Pillar Two top-up tax information return calculations in a proper top-up tax return.